RESEARCH

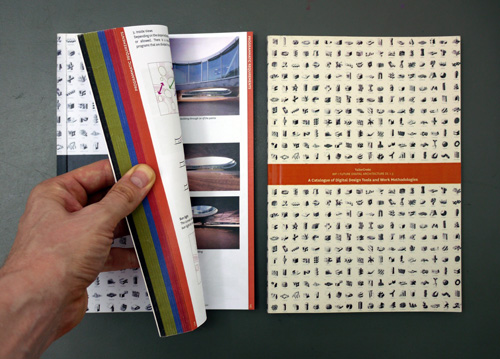

The Catalogue of Digital Design Tools and Work Methodologies

WP1 also investigates how the development of digital design tools changes the work methodologies of design teams today. In a second catalogue, The Catalogue of Digital Design Tools and Work Methodologies, WP1 describes and exemplifies three current and emerging work methodologies and key projects that employ these methods.

Catalogues

1. Traditional collaboration / standard tools

Construction industry relies on the expertise of many specialists orchestrated typically by an architect or a contractor. Since 1960’s computer aided design tools provide new platforms of communication between the involved specialists. Today there is a whole range of software available to draft and analyse design proposals.

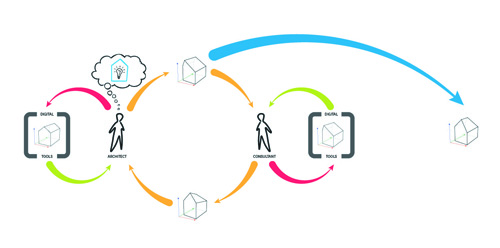

Typically the process starts with the architect documenting design ideas through 2D or 3D drafting and modelling. Exported to relevant formats for the specialist’s use, the proposal is then analysed with industry specific software. The specialist evaluates the result of the analyses and generates feedback for the architect, who then adjusts the design. Usually this ideas exchange happens several times among the architect and different engineers and slowly priorities are defined and the design is matured.

In essence this type of collaboration is “traditional”. Each specialist has his/her own sphere of knowledge and shares it “manually” through conversation or exchange of documents.

2. State of art collaboration / custom tools

Next to the still predominant collaboration methodology, described above, there is a new scheme emerging.

Standard software is supplemented by custom tools that enhance the software capability from purely analytical to generative. In this case the architect and consultants work together to develop software tools which generate optimized design solutions.

3. Future collaboration / generative tools

The research on current and emerging design methodologies led to the formulation of a speculative future scheme for architectural design; which will be based singularly on “generative design”.

Lars Hesselgren, the co-founder of the SmartGeometry Group, explains the new emerging method in the following words: “Generative design is not about designing a building. It’s about designing the system that designs a building.”

In this process, the architect controls all design parameters and he has the capacity to script sophisticated digital tools. Consultants are still involved, but rather as back-up to discuss solutions.

There are more custom tools, their performance is more advanced and there is an intense “communication” between the tools, so multiple parameters can be taken into account.

The Catalogue of Reasons for Architecture to Employ Complex Shapes

Though it is easy to demonstrate by comparison to other industries, the need in construction industry to find more efficient ways of producing complex shapes, the question to the architects still remains: Why should architecture need to employ complex geometries? Does architecture not function better inside rectangular walls?

WP 1 is answering these questions with a catalogue of over 40 architectural projects, called “Reasons for Architecture to Employ Complex Shapes”. The selected projects optimize certain building performances and surprisingly optimization most of the time means deviating from standard geometries into a richer world of shapes.

The catalogue identifies five main categories of reasons:

• Climatic Responsiveness

• Structural Efficiency

• Efficiency in Construction

• Programmatic Requirements

• Cultural and Commercial Requirements

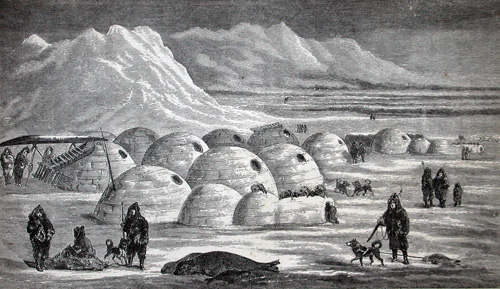

For example, one of the iconic examples for optimization through the application of a double curved surface is an igloo. The spherical shape is not dictated by aesthetics but by the rough polar climate.

Illustration from Charles Francis Hall’s Arctic Researches and Life Among the Eskimos, 1865.

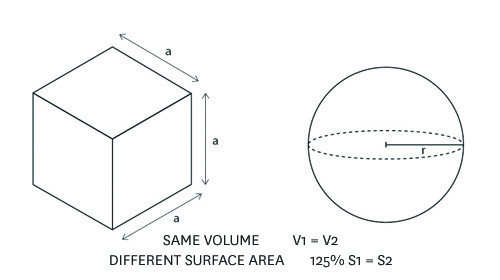

The surface area to volume ratio of a sphere is much lower than that of a cube of the same volume. In fact, a rectangular building of the same volume has 25% more surface area. Since the majority of a building’s energy losses and unwanted gains are through the surface material, a spherical shape can translate into drastic reductions in heating.